Physician Scientist Scholar Program Supports Six Scholars Pursuing Transformative Laboratory Research

UCSF’s Physician Scientist Scholar Program supports scholars pursuing transformative laboratory-based research to advance human health.

In the early morning hours on UCSF’s Parnassus Heights, the statue of Hippocrates, the "Father of Medicine," seems to fade into the wind and mist. Standing vigilant, he symbolically guides passersby in their search for medical knowledge. Hippocrates established some of the first standards in ancient Greek medical practice, emphasizing the transformation of theory into practice—an approach central to UCSF’s Physician Scientist Scholar Program (PSSP). Founded in 2013 by the School of Medicine in collaboration with clinical departments, the PSSP provides funding support for early career physician-scientists launching independent research careers that focus on conducting rigorous laboratory research focused on human disease. PSSP scholars also care for tiny preterm infants and for adults with cancer and life-threatening diseases.

Christina Homer, MD, PhD, a clinical fellow in the Division of Infectious Diseases in the Department of Medicine and one of the current PSSP scholars, emphasizes that funding alone is not enough for success. When Dr. Homer reflects on the writings of her namesake, she sees parallels to her quest for knowledge. Curiosity and persistence—her superpower—has led her to conduct critical research on fungal pathogens. Through the PSSP, Dr. Homer receives not only financial support but also a vital infrastructure for developing her research. The program helps her build exceptional research teams by hiring talented staff, allowing her research ideas to advance and flourish.

Dr. Homer’s patients come from arid regions in California – Salinas and the Central Valley – where dust carries infectious, sometimes fatal, soil-dwelling spores from the fungus Coccidioides into their respiratory tracts and causes the infection known as Valley Fever. Often asymptomatic, these patients present significant diagnostic challenges. Mycology, the study of fungi, is a small scientific field, leading to a lack of research on crucial elements like proteases, virulence factors, and the unique spherule structures formed by the fungus Coccidioides. In severe cases of Valley Fever, spores can even cross the blood-brain barrier. Since the dawn of medicine, one of the hardest aspects of being a doctor has been the inability to provide effective treatments. UCSF physicians, including Dr. Homer, frequently encounter complex cases of Valley Fever, facing the difficult challenge of caring for patients when answers remain elusive and effective treatments are lacking, a gap Dr. Homer is tackling with her research.

Elizabeth Crouch, MD, PhD is a pediatrician, neonatologist, and neuroscientist who studies blood vessels that are critical for normal brain development. Dr. Crouch’s lab is located in a modern spaceship-like building atop Mount Sutro—a fitting backdrop for someone who was once captivated by astronomy. Dr. Crouch applies single-cell RNA sequencing to understand human vascular development. In stark contrast to the sleek architecture, a photo wall displays the cherubic faces of young patients. Preterm infants and their families turn to Dr. Crouch for her expertise as she decodes the complexities of brain blood vessels. She speaks with reverence about the courage and enduring hope that parents maintain, even in the face of tragedy.

Through the PSSP, Dr. Crouch notes that her research continued to thrive during the COVID pandemic. She is focused on improving future care for the most fragile preterm infants. While one might assume that the PSSP application process was diminished during isolation, Dr. Crouch smiles shyly as she recalls being interviewed by a renowned Nobel laureate via Zoom—a moment that inspired her work.

On the Mission Bay campus, a lively group of new students gathers around the welcome tables on the ground floor of Genentech Hall, near the building's grand stone stairs reminiscent of ancient amphitheaters. Josiah Gerdts, MD, PhD, descends the steps with his backpack slung over one shoulder, blending in so seamlessly that it’s hard to believe he has already completed over 20 years of study.

As we weave through a maze of labs bustling with research staff and materials, the atmosphere resembles a crowded Thanksgiving flight, with overhead compartments stuffed to the brim.

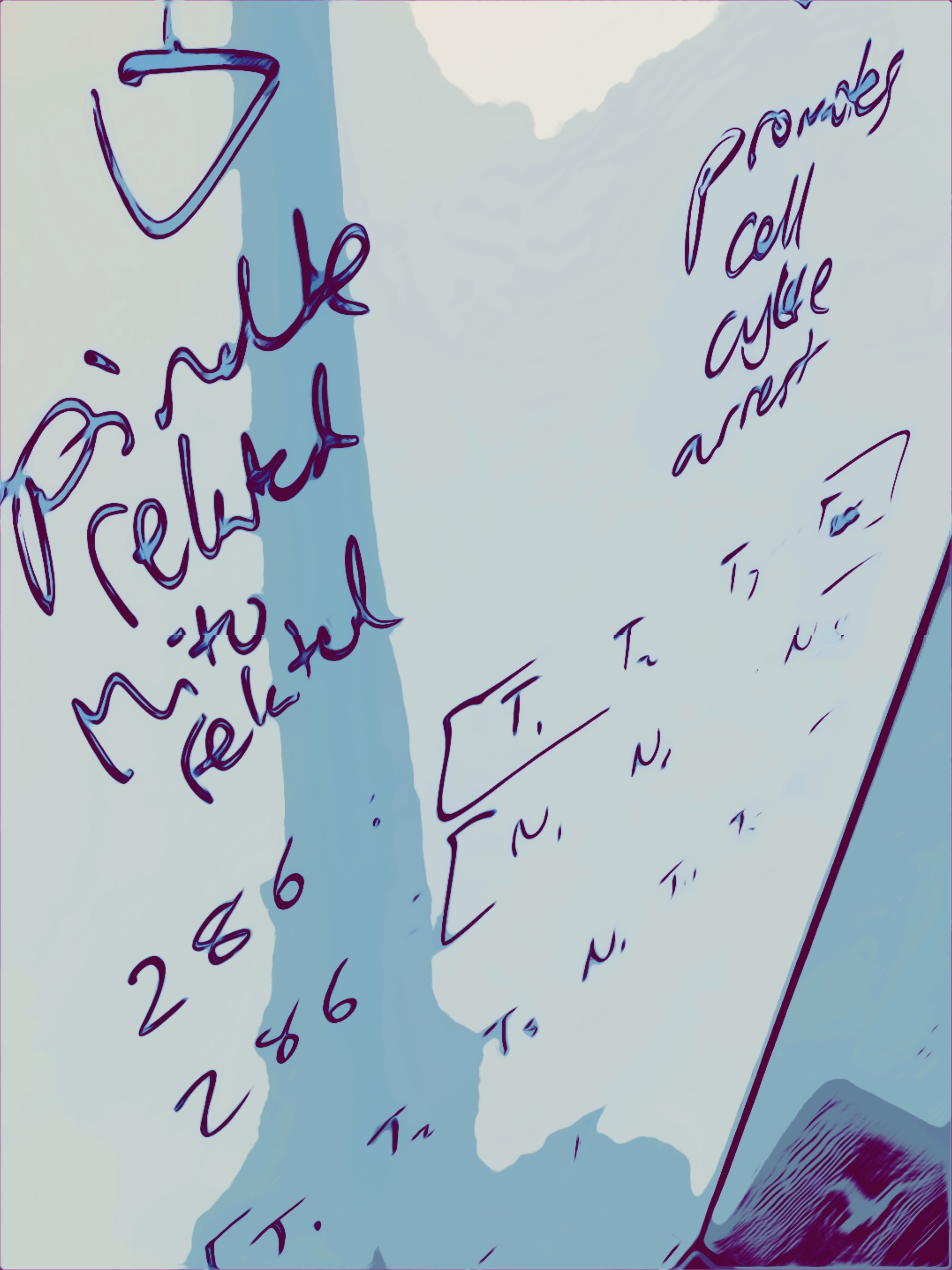

Dr. Gerdts, an autoimmune neurologist in UCSF's Department of Neurology, is pioneering new technologies to study how T cells cause autoimmune diseases. He is engineering live cells that interrogate T cells to learn how they react to thousands of specific molecules called antigens. Dr. Gerdts believes that mapping T cell antigen responses will be crucial to understanding autoimmunity and developing safer, more precise treatments for these devastating diseases. He is excited to be part of the PSSP program, which has energized his research into the complex mysteries of his patients' immune systems. Without hesitation, he looks forward to creating knowledge and tools that will allow researchers to target specific cells and develop more precise therapies. "Design, build, test," he says, grinning as he reflects on his passion for the intricate details of science.

Just down the road and nearly in the shadow of the Chase Center is the lab of Gabriel Loeb, MD, PhD. Dr. Loeb, a researcher in the Division of Nephrology in the Department of Medicine, feels incredibly fortunate to be a PSSP scholar. His work focuses on the genetic causes of kidney disease. He describes the PSSP as transformative, allowing him to ask questions and shape ideas much more quickly than he could have otherwise. Talking with him feels like conversing with a time traveler who has already accelerated into the future. He appreciates how the PSSP provides a crucial period of protected time for concentrated research.

Dr. Loeb points out that many people are unaware that kidney disease ranks among the top ten leading causes of death and is often asymptomatic until the late stages. He explains that while dialysis can save the life of someone with kidney failure, life expectancy on dialysis is limited, and it is a challenging treatment to undergo. The goal of his work is to help prevent and treat kidney diseases for which we currently have no effective therapies. In contrast to cancer and immunologic diseases, few physician-scientists are focusing their careers on kidney disease.

He also notes the declining number of MD/PhDs in the United States, suggesting this trend could hinder future research on disease pathogenesis and the development of new therapies. However, these challenges seem to invigorate him. He recalls being “that kid” who constantly asked why, often driving his teachers to distraction.

With pride, he discusses his research into the molecular mediators of kidney disease and fondly remembers the pivotal moment during his junior year of college when he shifted his focus from engineering to the allure of biology.

In the UCSF research buildings surrounding Koret Quad, you can find Jonathan Ostrem, MD, PhD, whose office overlooks the tranquil, tree-filled space. Like his fellow PSSP scholars, Dr. Ostrem embodies a vision for what is possible, coupled with the tenacity to bring his ideas to life.

As an assistant professor in the Division of Oncology in the Department of Medicine, Dr. Ostrem’s journey began with an interest in 3D structural art, which eventually led him to biochemistry and now to his current role as a thoracic oncologist and chemical biologist. Ostrem’s lab focuses on using cutting-edge chemical methodologies to make better cancer therapies. In July 2024, Dr. Ostrem published an article in Nature Chemical Biology that follows up on a fundamental discovery of the first inhibitor of a protein called KRAS that he made as a graduate student in the UCSF Medical Scientist Training Program while working in the lab of Kevan Shokat, PhD. KRAS mutations drive the abnormal growth of many cancers including those of the lung, pancreas, and colon. Dr. Ostrem's pioneering studies in the Shokat lab led to the development of the first KRAS inhibitors and galvanized a decade of advancements in molecular cancer research in industry and academia.

One notable aspect of his recent paper is its emphasis on the importance of mentorship and career guidance—an element prevalent in many labs, particularly within the PSSP. Dr. Ostrem artfully connects his ideas with those of his mentors and colleagues, acknowledging the collaborative spirit that drives success in research. In his retrospective, he writes, "Nearly all success stories stand on the shoulders of failed attempts," adding that "it would be impossible to count the number of times fortune swung in our favor along the way."

Dr. Ostrem discusses the evolution of targeting first-generation KRAS molecules and emphasizes the critical balance between risk and benefit in cancer treatment. He highlights a recent discovery: patients who receive palliative care earlier in their treatment actually live longer. This finding underscores the importance of integrating palliative care into the treatment process.

By continually asking what is meaningful while caring for patients with inoperable lung cancer, Dr. Ostrem bridges the gap between bench research and the clinic. This approach brings a necessary harmony to his work, especially as he navigates the somber reality of treating patients whom he knows he cannot cure.

On the upper levels of the UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences, Kristen Berendzen, MD, PhD, from the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, studies the neurobiology of social behavior in aging and disease. With degrees in both neuroscience and art history, her striking screensaver rivals the framed artwork throughout the boldly designed building.

Dr. Berendzen, who grew up in a family without any health or medical professionals, initially considered further studies in European art. However, engaging mentors and compelling research opportunities changed her course. She continually explores timeless questions about neurodegenerative diseases, including how we navigate the world and what contributes to healthy aging. Her research on rodent social behavior reveals parallels to the neural mapping underlying human attachment and empathy.

In the lab, Dr. Berendzen investigates novel therapeutic targets for neurodegenerative diseases and neuroendocrine mediators of behavior. The PSSP provides vital support, affirming the value of her work. When asked about her experience as a PSSP scholar, she expresses immense gratitude, feeling as though "the gods have smiled" upon her.

Dr. Berendzen recognizes that the research journey is often lengthy, with no clear horizon in sight. As she glances toward the setting sun, she reflects on the remarkable creativity in science and her ability to work both microscopically with neurons and on a macro scale with the cultural themes that echo throughout history.

The path of our scientific discoveries remains uncertain. However, the scholars in the Physician Scientist Scholar Program inspire a sense of wonder and optimism. Meeting these PSSP heroes, who embody both intellect and compassion, offers a glimpse into the future of medicine that is truly uplifting.

Perhaps the ancient Greeks would no longer caution us about flying too close to the sun. Instead, they might encourage us to soar even further and faster, measuring our journeys with equal parts hope for the past and excitement for what lies ahead.